SOME DAYS, AS SHE WRAPS UP THE LAST SIX MONTHS of her UBC family practice residency training, Dr. Emma Garson discovers nuggets of her family history from certain patients.

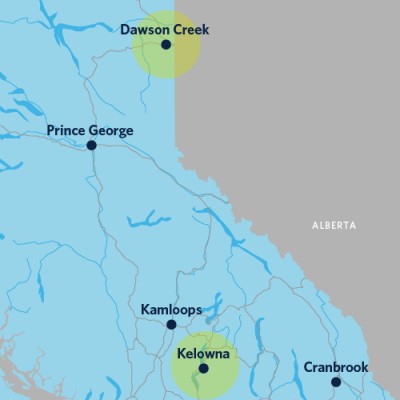

Dr. Garson was born in and grew up in Kamloops, a city of approximately 90,000 residents in BC’s Thompson-Okanagan region. After earning her medical degree from the Southern Medical Program (SMP) based at UBC Okanagan, Dr. Garson is now completing her two-year residency in her beloved hometown. She splits her time between practicing and learning at Aberdeen Medical Centre and Royal Inland Hospital.

“There’s not a ton of Garsons in town,” she says. Occasionally a new patient noticing her last name shares stories about her kin, including her father Bruce who passed away in 2013. “So I pick up my own family history just by practising here.”

Dr. Garson didn’t come from a medical family. Her mother worked in IT at Thompson Rivers University, while her dad — a jack-of-all-trades — was a semi-pro hockey player, a cop and worked in the restaurant industry. Yet no one who knew Dr. Garson growing up in Kamloops would be particularly surprised that, by the end of this year, she’ll be a licensed physician.

Dr. Garson didn’t come from a medical family. Her mother worked in IT at Thompson Rivers University, while her dad — a jack-of-all-trades — was a semi-pro hockey player, a cop and worked in the restaurant industry. Yet no one who knew Dr. Garson growing up in Kamloops would be particularly surprised that, by the end of this year, she’ll be a licensed physician.

“If you asked my mom she would definitely say I was a nurturing child,” laughs Dr. Garson. With friends growing up, “I would be like the mom of the group. I liked that role and I like looking after people.”

At 16 the idea of pursuing medicine began to tug at her. When her grandmother, who lived nearby, had a tumour removed, Dr. Garson moved in with her for nearly a month to help her recover. When her father’s health declined due to Alzheimer’s, she helped look after him as well.

For Dr. Garson, community has long been important. “I’ve never been one that’s needed to see the sights or travel around the world, or be in a big city,” she explains.

When exploring options for medical school, the SMP appealed to Dr. Garson because of its smaller classes and links to clinical training partners in the Kamloops region. The SMP, she says, delivered on her desire for a sense of community that she feared would be missing at a larger university.

Every year, UBC admits 288 new students to its undergraduate medical program. The bulk attend the university’s Vancouver campus, but the remainder — 32 students per region — attend satellite programs at the University of Victoria, the University of Northern British Columbia and UBCO. Established at UBCO in 2011, the SMP was designed to help medical students “meet the health-care challenges of tomorrow,” and serve the needs of communities throughout the Interior Health region.

“As a medical student in a smaller community,” explains Dr. Garson, “if you’re interested in being a surgeon in the future, there’s lots of opportunity to be a first assist. You might be driving the camera, so the surgeon can see what they’re doing, or retracting skin. You can really be part of the action.

“In the clinic in our community,” she continues, “I do minor procedures independently. I’ll do a skin biopsy on my own or an IUD insertion for contraceptive management. So I get to do some procedural things which I enjoy. It’s not necessarily everybody’s cup of tea. But certainly, at our site and just the smaller sites in general, there’s lots of opportunity to be hands-on.”

Now, as a family medicine resident close to achieving her dream of being a full-fledged physician, Dr. Garson currently rotates between the Aberdeen Clinic and Royal Inland Hospital. She’s getting a taste of many medical specialties including surgery, internal medicine, emergency medicine, psychiatry and obstetrics.

As she started transitioning from medical school to residency, Dr. Garson was more supervised at first. Now, doing full-care family practice at Aberdeen, she has more autonomy. “If I’m not confident about something, I can pick the brain of my preceptor [medical supervisor] and run my plans by her.”

By nature, Dr. Garson describes herself as someone with a generalist personality and as a “fixer.” Those traits dovetail nicely with family medicine, which demands competence in a variety of medical skill sets. Tailoring her future practice to the needs of Kamloops, she sees a strong possibility that she will focus on palliative care.

“I like doing longitudinal care. You get to know your patients well. You see them through the good, the bad and everything in between. To me, that’s a privilege.”

Recently married, Dr. Garson was so confident in her opportunities to practice medicine in her hometown after her SMP education that she and her husband bought a home. “There’s such a shortage of family doctors here in Kamloops and BC in general. So there’s value in me staying here.”

An avid golfer like her partner — there are seven courses in Kamloops — Dr. Garson looks forward to the work-life balance a medical career in Kamloops offers. Since buying her home, she’s been laying down a new floor and doing other renovations.

And, as a “fixer” at heart, she looks forward to a life-long career in Kamloops where she’ll also have the opportunity to repair the health of those in her community.

The SMP had a number of attractions for Smith; in addition to bringing her closer to family in Kelowna and Kamloops, the program offers a special focus on rural medicine. In the tiny towns and villages where Smith grew up, health care professionals didn’t always seem personally connected to community. But she wants to be a different, more integrated and community-involved doctor — the kind the SMP trains students to be.

The SMP had a number of attractions for Smith; in addition to bringing her closer to family in Kelowna and Kamloops, the program offers a special focus on rural medicine. In the tiny towns and villages where Smith grew up, health care professionals didn’t always seem personally connected to community. But she wants to be a different, more integrated and community-involved doctor — the kind the SMP trains students to be.